Section VII: Governmental Correspondence

Governmental correspondence is divided roughly into three kinds:

-

the army,

-

the navy, and

-

the departments of the government which are under the civil service.

The civil departments of the government have no definite rules for the preparation of their correspondence, and the secretary must accustom himself to the usage of the particular office in which he happens to be, in the same way that he would if in an ordinary business office.

The first sentence of the chapter relating to navy correspondence in the navy handbook is worth quoting and remembering:

“Correspondence shall be minimized as much as is compatible with the public interest as regards the number of letters written and their length.”

For official correspondence in the navy, the regulations prescribe typewriting paper 8 x 10½ inches in size, instead of the standard 8½ x 11 inches paper which is generally used in private offices. Consequently, the secretary will be obliged to make a slightly different adjustment of the marginal stops on the typewriter. For carbon copies for the files, green tissue sheets are used.

After the date of the letter has been written the word “from” is placed at the left-hand margin followed by the full name and title of the writer. On the line below, the word “to” is placed, followed by the official designation of the office or official addressed. Following the address, the subject of the correspondence should be written across the page in the way the communication will be indexed for filing. In acknowledging and referring to official communications, the file number and date should be included in the “Reference.” The file number of the letter should be placed in the upper left-hand corner about one inch from the top and one inch from the left edge of the page, followed by the initials of the section preparing the correspondence. Letters should be written single space with one double space between paragraphs. Paragraphs are to be numbered and sub-paragraphs lettered. The complimentary opening and closing of the letter is omitted.

Every person in the Navy making an official communication of any kind to any superior authority other than his immediate commanding officer must send the communication to his commanding officer to be remarked upon by him and forwarded.

The forms mentioned are used only in communications passing between different branches of the navy or between the navy and other branches of the government using the same forms. In writing to those who do not use such forms, the letter may be written as is customary in the ordinary business office.

The general regulations regarding the army correspondence are similar, with minor exceptions such as that providing that communications consisting of less than eight lines may be double spaced. One requirement which might profitably be adopted by the business world is that calling for a description of the inclosures not fully described in the body of the letter itself.

On all copies except the original and first carbon of letters for the signature of the Secretary of War, the Assistant Secretary of War, or the Chief of Staff, and of many for the Adjutant General, the initials of the division and immediately under them the initials of the officer responsible for the preparation of the paper, shall be typed in the upper right-hand corner. These initials shall be typed on all copies of memoranda for the Chief of Staff. The secretary's initials below the body of the letter, and to the left, shall appear on all copies on which the officer's initials appear, but not on the others. The date is omitted on all letters prepared for the signature of the Secretary or Assistant Secretary of War, or the Chief of Staff. The date is inserted after the signature of the letter.

The secret or confidential stamp is placed both at the top and bottom of the pages of all secret and confidential papers. Such papers are always sent by registered mail or by a special messenger. The secretary is held responsible for the careful comparison of any quotation before submitting the finished typed matter, and is expected to read over the finished work, to correct misspelled words and typing errors, thereby relieving the dictator of such details.

Another difference between the usage of the business office and the Army is the requirement that in assembling the papers which accompany a letter, the envelope should be placed vertically among the papers and not horizontally, in order to prevent the edges of the envelope from becoming soiled.

All communications which are to be signed by the Secretary of War or the Chief of Staff must be typed on machines equipped with élite type. This provision is necessary in order that minor changes in signatures and similar corrections may be made in the office of the Secretary or the General Staff without necessitating the return of the papers to the division preparing the document originally.

All communications which are to be signed by any member of a division should be on the division stationery. Stationery with the heading “War Department, Office of the Chief of Staff, Washington” without reference to any division of the General Staff will be used for communications to be signed by the Secretary of War or the Assistant Secretary of War. The words “In reply refer to” will be typed or printed in the upper left-hand corner of all letter paper.

The Army handbook suggests the following check as an aid to stenographers and secretaries in insuring the correct and accurate preparation of papers. It might profitably be used by every stenographer.

-

Have the original papers been definitely disposed of?

-

Have the papers been compared?

-

Has the proper stationery been used?

-

Are there a sufficient number of copies?

-

Have the initials of the dictator and stenographer been typed on the proper copies?

-

Have the file reference numbers been typed on the proper copies?

-

Have the inclosures been noted and are they all attached?

-

Are the copies assembled according to instructions?

-

Have the papers been securely fastened to prevent separation in transit, and are they arranged with their edges even so that no papers will be exposed?

-

Have all carbon copies been marked to show their proper distribution?

-

Are there any unnecessary carbons attached?

Secretarial Problems: Review and Research Questions

-

How is governmental correspondence classified?

-

What is the size of the paper prescribed for the official correspondence of the navy? What is the color of the second sheets?

-

When an officer communicates officially with some superior other than his own immediate commanding officer, through what channels must the communications pass?

-

How are the envelopes to be placed among the unsigned correspondence? How does this differ from the ordinary commercial practice?

-

What are the points suggested by the army handbook as an aid to secretaries in insuring the correct preparation of papers?

-

What is a file number, and what is its purpose?

Secretarial Problems: Laboratory Assignments

To the Secretarial student: It will be necessary for you to detach the problems in this section from the activities of our business, and assume that for the time being you are in the Government Service.

-

Type the following in the proper form:

AG 211, 221 Misc. Div. WPD 426 - Current date.

MEMORANDUM FOR THE CHIEF OF STAFF:

Subject: - Handling registered and insured mail in Military Camps. I. Papers accompanying. Memorandum to the Chief of Staff from The Adjutant General of the Army, dated January 24, 1920. Recommendation of Camp Inspector, Camp Upton, N. Y. II. The problem presented. Shall steps be taken to have post offices at Camps send regular notices of registered letters and insured parcels and shall the present mail orderly system be discontinued. III. Facts bearing upon the problem. 1. The Camp Inspector, Camp Upton, recommends that regular notices be sent by post office. 2. The Adjutant General states that he agrees with Camp Inspector. 3. Many complaints have been received. 4. Postal authorities request that all instructions be followed. 5. The present system is satisfactory at most camps. IV. Opinion of War Plans Division. That no change in the existing procedure be made at this time owing to the unsettled conditions. V. Action recommended. Memorandum for The Adjutant General of the Army. VI. Concurrence. The Adjutant General (Colonels A and B) concurs. Colonel, General Staff, Acting Director, W. P. D.

-

Type the following in proper form:

Navy Yard, Puget Sound, Wash., Hull Division,

(Date.) To: Commandant. Subject: Quick-drying paint. References: (a) Bu. circ. let. 4048-A. 279 (AP), 7-27-11. (b) Bu. circ. let. 4048-A. 306, 1808-A (13191-A.505) (CH), 3-14-12. (c) Bu. circ. let. 1808-A. 912 (13181-A.477) (CU), 2-12-12. Inclosures: 2. l. I request that the Bureau of Construction and Repair furnish formula for manufacturing slate-color, quick-drying paint mentioned in the first paragraph of reference (c). 2. Also request information as to the proper formula for boot topping on battleships. The second paragraph of reference (c) states that black, quick-drying paint is used for boot topping on vessels painted slate color. Reference (b) gives black boot topping formula for use on torpedo boats, destroyers, and colliers, but states nothing about modifying previous instructions regarding boot topping for battleships, the last instructions received on that point being in reference (c). Attention invited to inclosure (B) showing samples of boot topping used on ships at the yard, and that mixed according to reference (c). Arthur Black. 1st indorsement. Navy Yard, Puget Sound, Wash.,

(Date.) To Bureau of Construction and Repair. Subject: Quick-drying paint. Inclosure: I. 1. Approved and forwarded. E. F. G---.

-

Dictation.

-

Transcription.

Section VIII: Suggestions for Making Correspondence Effective

In addition to transcribing in perfect form - English, punctuation, spelling, mechanical arrangement - the secretary will be expected to write many letters from brief verbal instructions of his employer, or from notations on the margins of letters. The quantity of correspondence he will handle in this way will depend upon the ability he displays in his first assignments, his aptitude in grasping the employer's point of view, and his skill in putting his thoughts in good English.

At first these letters will naturally be of a routine nature; but the impression which the employer gets from these first attempts will go a long way toward securing his confidence in his secretary's ability. The secretary should be alert to catch the meaning of any instructions given, taking shorthand notes of important matters as his employer dictates. It is often difficult to follow the employer under such circumstances, for he has a background and point of view not possessed by the secretary. The secretary must be sure that he understands the situation, and any questions necessary to clear up a questionable point should be asked at the time it is dictated. In taking down instructions of this nature, it is well to use the employer's exact words rather than to brief the instructions as you go. You can then read the instructions carefully and decide upon the form your letter will take. In doing this be careful to observe the following points:

Arrange the ideas in their logical order. Be sure that you understand all the factors of the correspondence or the matters under consideration. If you do not, you cannot be expected to write about them intelligently. Should any questions arise in your mind that you cannot answer from the instructions given, take them up with your employer and get all the facts.

Instructions given verbally are apt to be more in detail then brief notations, since the employer, having in mind what he wishes to say, will simply note the important facts and leave the language to the secretary. Care must be exercised to use correct language. In writing any business letter take into consideration the reader's ability to understand. The facts should not only be stated in as exact words as possible, but the words themselves should be simple and easily understood. Getting an absolute understanding of the idea of the letter is fundamental. Most of the letters the secretary will write will possibly deal with one subject only and will consequently be easily constructed. Where a letter deals with more than one subject it is well to make an outline of the subjects so that you can treat them in logical order and dispose of each fully as you come to it. Go over your outline and compare it with the original instructions to see whether you have incorporated all that was intended. If there are figures, prices, or data of any kind to go into the letter that can be verified from other sources, this should be done. These instructions naturally are for the inexperienced secretary. It may seem roundabout but details seem necessary, and the technique is correct. As experience is gained and judgment developed, the process will be shortened.

A letter should be as brief as possible consistent with giving the complete details for its proper understanding by the reader. It should be businesslike without being brusque, mechanical, or discourteous. Its tone should be in keeping with the occasion. Avoid overworked words and meaningless phrases. Such expressions as “we are in receipt of your favor,” “we beg to acknowledge receipt,” “and in reply would say,” “we beg to state,” have no place in modern business correspondence. They are relics of a bygone age, despite the fact that the average business letter of today is cluttered up with any number of them. Much more effective expressions can be used if a little study is given to the matter. If you feel that you are weak in English, you will find it a very useful exercise to take any one of the dictation books now on the market, go through a letter, and underline each expression that you think is meaningless and out of date. Rewrite the letter thus treated, aiming to incorporate the same ideas, but in language that is more appropriate. You can submit these to your English teacher for criticism. It is impossible to estimate the waste of time by correspondents, secretaries, and even business men themselves, in dictating a letter full of expressions that contribute nothing to the meaning, simply because of a mistaken idea that business letters should be written in the language of old-time books on business correspondence. The language of a business letter should be live and vital; it should be good English applied to business situations.

Many secretaries make the mistake of thinking that letters should conform to a certain formula. If you will write a letter much as you would state the same facts or ideas verbally, your letter will be much more effective. A good business letter always reflects that evasive quality which we term personality. It should contain ideas, not mere words. The briefer your statements are, if clear, the better. Test every letter you write by the following standards before turning it over to be read by your employer.

-

Does it contain all the elements essential to a complete understanding of its content?

-

Is it expressed in clear and forceful English?

-

Is it coherent?

-

Does it convey the idea adequately?

-

Is it typed correctly?

If you are fortunate enough to have a stenographic assistant, you will test all letters that you dictate by the foregoing standard, the same as if you had written them yourself.

Secretarial Problems: Review and Research Questions

-

Name the five tests to be applied by the secretary to a business letter.

-

If you should determine that a letter is weak in any of these factors beyond your control, what steps will you take?

-

What is meant by “meaningless expressions”? Give five examples.

Secretarial Problems: Laboratory Assignments

-

Write the following letters at the suggestion of the manager:

-

To the President of the State College declining an invitation to address the students (on a given date to be filled in) on the subject of “The Problem of the Manufacturer.” Reason, absence from the city.

-

To the Commodore Hotel, New York City, asking that room and bath be reserved for him on the fifteenth of next month.

-

Dictation.

-

Transcription.

Concrete Suggestions for the Letter Writer, part I

Punctuation, spelling, wording, etc., reflect, favorably or otherwise, upon the reputation of the house.

Good letter writing involves three factors:

-

the writer,

-

the subject, and, most important,

-

the reader.

For the sake of the reader, the writer must:

-

Present his subject clearly and forcefully

-

Refer to previous correspondence accurately. (Include dates and figures when necessary.)

-

Eliminate useless words.

-

Avoid stereotyped phrases.

-

Make the letter please the eye. To this end, arrangement, neatness, and perfect workmanship should receive thoughtful attention.

Dates - Never omit the date. Do not abbreviate the months. Do not use d, nd, rd, st, or th after the day of the month. (Write June 3, not June 3d.) Do not use ult., inst., or prox., but name the month. (Write October 25, not 25th ult.)

Address - Address an officer as Mr. and place his title and the name of the institution on the line below. Example:

| Mr. Louis J. Weil, |

| Vice-President UnionExchange National Bank. |

Address an employee without title, by the term Mr., and place the name of the institution, preceded by ”c/o,” on the line below. Example:

| Harvey Murray Esq. |

| c/o Corn Exchange Bank. |

When replying to a company letter signed by an officer or clerk, address the man himself. Example:

| Mr. Arthur Hastings, |

| President Great Eastern Paper Co. |

Not - Great Eastern Paper Co., Attention of Mr. Hastings. But when writing for documents or otherwise originating the correspondence, it is often well to follow the latter form, which makes the letter primarily a company matter, to be attended to even in the officer's absence.

When firm names are composed of two or more surnames, or surnames followed by Co., Bros, etc., omit the title Messrs. Examples: Weir & Foley; Smith Bros; H. & W. B. Drew Company.

In firm titles, spell out or abbreviate and according to letterhead or signature of firm, but when there is nothing to prove that two individuals are a firm use Messrs. Examples: Messrs. R. L. & N. B. Clapp; Messrs. William & Henry James.

Write Christian names in full, unless the contrary practice is indicated by letterhead or signature of the person addressed.

Abbreviate Co., Bros., Pres., Treas., except in text, when spell out. Write out Street, East, West, Broadway, etc. Write out Avenue with a short address, but abbreviate a long one. Examples: 24 Lexington Ave., 1 Avenue J.

Date Line - Write New York City, not New York, N. Y. Numbered streets should preferably be written out. Example: 11 East Seventy-fourth Street. This form avoids any confusion that may arise from the house number and the number name of a street following each other as, 11 74 Street. The above rules are for letters. In the case of envelopes, be guided by the eye, and the desire for well proportioned spacing. Never use rd, th, etc.

Salutation - Firms such as Gimbel Brothers, Daniel Reeves, Inc., and Harrods, Ltd., should be addressed Gentlemen. An estate should be addressed Gentlemen. Example: Estate of William Dick, Gentlemen:

Use Gentlemen, not Dear Sirs. My dear Sir is more formal than Dear Sir. Use My dear Madam in preference to Dear Madam, in addressing a woman, either married or single. Use My dear Mrs. Brown or Dear Mr. Brown in addressing a woman, or man known personally. Use Mesdames when addressing two or more women. Write Mrs. ? when uncertain whether a woman is married or single. This will imply doubt, explain the error, if one has been made, and will probably call forth the desired information for future use. Use capitals for the first word of the salutation, and for the word that stands in place of the name. Example: My dear Sir: Use a colon after the salutation. There is no reason for adding a dash. Example: Dear Sir: The salutation is rarely used on a memo. in inter-house correspondence.

Complimentary Close and Signature - “Yours very truly” is the best complimentary close for formal letters. “Very sincerely yours” may be used only when personal relations exist. The complimentary close should be started midway between the margins, two spaces below the last line of the letter. When an officer's title is given, it should be placed about five lines below and four spaces to the right (unless, in the case of a narrow letter, this brings it beyond the right hand margin.) Manager, Bond Department is written in full.

Initials, Inclosures, Etc. - Initials should appear in the lower left hand corner, on a line with the body of the letter, and about six spaces below the last line. Three sets of initials are necessary and should be placed in the following order:

-

Head of the department - initials in full.

-

Below, the dictator - initials in full.

-

On a line with the dictator's initials, separated from them by a dash, the last initial of the stenographer. The word “inclosure” should be placed two spaces below the initials. It should be written out in full, in either red or blue. Example:

Secretarial Problems: Review and Research Questions

-

What factors are involved in good letter writing?

-

For the sake of the reader, what factors must the writer keep in view?

-

Write the proper salutations for the following:

-

The National City Bank, New York City.

-

John Wanamaker, New York City.

-

Marshall Field & Co., Chicago.

Secretarial Problems: Laboratory Assignments

-

Make a diagram of the proper form of a letter showing place of date, name and address, salutation, body of letter, complimentary close, signature, additional references.

-

Dictation.

-

Transcription.

Concrete Suggestions for the Letter Writer, part II

Spacing - Letters should be carefully blocked, paragraphs indented, and right and left margins equally spaced.

Long Letters should begin near the top of the page, about six spaces below the imprint, and margins may be as narrow as one inch, if this will enable the stenographer to accomplish the much desired “one page letter” without running the text too near the bottom of the sheet. If a second page is necessary care should be taken not to begin a paragraph at the bottom of the page, unless there is space for three of its lines.

Spanish and Portuguese letters to South America should have very wide margins.

Short Letters should begin eight or ten spaces below the imprint, and have margins of about two inches. When letters are blocked, they must be single spaced, with double spacing between the paragraphs.

Paragraphs - Where action is desired or attention is to be attracted, short paragraphs are best. When the object is to convince, conciliate, or give smoothness or delicacy of touch, the long paragraph is usually employed.

Subject -Whenever practicable, the subject should be placed in the center of the page, four spaces above the address. Example:

| Consolidated 4% Mortgage of 1910. |

Except in unusual cases, a letter should never embody more than one subject.

Revision - The secretary must go over the letter carefully to see that it is perfect in wording and appearance and then place a tiny check against his initial. If the letter is satisfactory the dictator also checks it and gives it to the signer, who alone is responsible to the officer whose name is signed.

Secretarial Problems: Review and Research Questions

-

Give the general rules for spacing of letters of different types.

-

How should a letter be paragraphed?

-

Where is the subject of a letter written?

-

How should the second page of a letter be treated?

-

Why is revision necessary?

Secretarial Problems: Laboratory Assignments

-

Dictation.

-

Transcription.

Concrete Suggestions for the Letter Writer, part III

Words and Phrases - Stereotyped words and phrases should be constantly guarded against, for they do more than anything else to endanger effective letter writing.

Overworked Phrases - Avoid such phrases as:

-

“Just a line to inform you that”

-

“Yours of,” “Your esteemed favor,” etc. (say “Your letter”)

-

“Your favor at hand”

-

“Your letter has been received and contents noted” or “In reply to same”

-

“We beg to acknowledge” or “We beg to say”

-

“Pursuant to yours of even date”

-

“We hand you” for “We inclose”

-

“I will say” or “I could say” for “Allow me to say”

-

“In reply would say” for “In reply allow me to say,” (or better still, say what must be said without awkward or unnecessary prefaces).

-

“At the present time” for “At present”

-

“We have investigated our records and find” for “ We find”

-

“We regret to learn,” “We apologize,” etc., for “We regret”

-

“Thanking you in advance”

-

“Hoping to hear from you”

-

“Awaiting your reply”

-

“Due to this cause” for “On account of this cause”

-

“Your good institution,” “Your good self,” etc.

Superlatives - Avoid superlatives. Example: Use “Your plan is excellent,” instead of “Your plan is most excellent.” Be careful about the use of overworked words, such as; ideal, forceful, advantages, efficiency, earlier, hereby, therefrom, therein, thereupon, herewith, hereto, etc. Avoid the too frequent use of these latter words at the beginning of sentences and of “trusting,” “hoping,” in the complimentary close. “Advise” is used to excess, not only when “inform” is meant, but often when the writer has no information or advice to transmit.

Repetition - Repetition of a word or phrase is to be avoided as a general thing, but sometimes it is necessary to make a sentence clear. Avoid the use of “same,” “the above,” “the same,” (sometimes “the former,” and “the latter”) in place of “it” or “they” or the subject matter itself.

Secretarial Problems: Review and Research Questions

-

What is meant by ”stereotyped” words and phrases? Give five illustrations of these.

-

Furnish substitutes for the following:

-

“Just a line to inform you that”

-

“Your letter has been received and contents noted”

-

“Pursuant to yours of even date”

-

“I will say”

-

“Hoping to hear from you”

-

How may repetitions be avoided?

Secretarial Problems: Laboratory Assignments

-

Recast the following letter, eliminating all overworked phrases and expressing the ideas in as clear and forceful language as you can.

We are in receipt of your favor of even date and in reply to same would say that owing to a strike in the factory we cannot comply to your request to ship goods within the next two or three weeks. We expect to resume operations within the near future but cannot state the exact date. Hoping this will be satisfactory to you, we remain, Very truly yours.

-

Dictation.

-

Transcription.

Concrete Suggestions for the Letter Writer, part IV

Shall, Will, Should, Would - To express futurity or expectation (without expressing willingness, desire or determination) the following forms are used:

| I shall | We shall |

| You will | You will |

| He (or it) will | They will |

Examples:

| “I shall be glad to hear.” | not | “They will be glad to hear.” |

| “I will be glad to hear.” | | “They shall be glad to hear.” |

To express determination, desire or willingness, use:

| I will | We will |

| You shall | You shall |

| He (or it) shall | They shall |

Examples:

| “He shall pay that bill if I,” etc. |

| “You shall stay out of this territory.” |

| “It shall be done.” |

Questions - When the subject is in the first person, shall is always used, except in repeating questions addressed to the speaker.

| “Will I let you have that discount?” | “Why of course I will.” |

| “Shall we continue to mail the lists?” | “We will mail -.” |

| “Shall I return the bonds?” | “No, we will do so.” |

Examples:

When the subject is in the second or third person, use the form that will be used in the answer.

Examples:

| “Shall you go on the 8:20 train?” | “I shall (or shall not) go.” |

| “Will he come?” | “He will come.” |

| “Will you lend the money?” | “I will lend the money.” |

In indirect discourse, use the form corresponding to that employed in the direct quotation.

Examples:

| Letter reads; “I shall arrive on the 8:20 train.” |

| Quotation reads; “He said in his letter that he should arrive.” |

| Telegram reads; “I will grant you the favor.” |

| Reply reads; “You telegraphed that you would grant me the favor.” |

In conditional clauses, introduced by “if” or “whether,” shall is used to express futurity in all persons.

Examples:

| “If he mails me the check I shall be glad to send,” etc. |

| “If he should leave the company, we shall probably,” etc. |

Should and would are used in the same way as shall and will.

Examples:

| “We should appreciate any information,” expresses futurity. |

| “We would gladly co-operate” expresses desire or willingness. |

When possible, use the forms shall and will, in preference to should and would.

Secretarial Problems: Review and Research Questions

-

To express futurity or expectation, without expressing willingness, desire or determination, what forms are used? Give illustrations.

-

Which forms express determination, desire or willingness? Illustrate.

-

When the subject is in the first person, is “shall” or “should” used? Give illustrations.

-

Which forms are given the preference, shall-will or should-would?

-

Correct the following:

-

I will arrive on the 10:20 train.

-

They shall be glad to hear.

-

I will be glad to learn.

-

If he mails me the papers I will be glad to go over them.

Secretarial Problems: Laboratory Assignments

-

Dictation.

-

Transcription.

Concrete Suggestions for the Letter Writer, part V

Can denotes power or ability and should not be used for may, which denotes permission. Example:

| “Can I have an interview” should be “May I have an interview?” |

Concern should not be used for business, company, or firm.

Couple should not be used for two (except when married people are referred to.)

Deal should not be used for transaction or arrangement.

Do not and does not should be used instead of don't and doesn't in business letters.

Either and neither - See Or or Nor.

Farther is used in the sense of more remote, at a greater distance. Examples:

| “The farther end.” |

| “He went still farther.” |

Further is used in the sense of moreover, in addition. Examples:

| “Further, he suggested.” |

| “A further reason.” |

Got should be used only in the sense of secured. Never use gotten. Received may often be used as a synonym. Examples:

| “I got your order.” |

| “We are obliged to leave.” | not | “We have got to leave.” |

| “Have you the time?” | | “Have you got the time?” |

Locate and located are wrongly used in the place of find, situated, or placed.

Or, Nor, Either, Neither.

Or indicates an alternative, and is used with either, which means one of two things. Examples:

| “We can sell stocks or bonds.” |

| “Either will be satisfactory.” |

| “Either one or the other.” |

Nor is used in a negative sense.

Neither is followed by nor, never by or. Examples:

| “We do not speculate nor do we invest in stocks.” |

| “Neither cases nor cabinets are satisfactory.” |

| “Neither one nor the other.” |

Party or parties should be used only with legal terms.

Posted is too often improperly used for informed.

Per is used in connection with words of Latin form. Examples:

Do not use per in place of by, or say “per week;” use “a week.”

Per cent should not be used as a noun; use percentage. Example:

| “Only a small percentage.” | not | “Only a small per cent were present.” |

Persons - In some cases persons is better than people. Example:

| “Some of the persons on our mailing list.” |

Please should be used rather than kindly.

Proposition should not be used when meaning suggestion, idea, plan, etc.

Quite means entirely, wholly, and should not be used in the sense of rather. Examples:

| “It is quite satisfactory.” | not | “It was quite dark.” |

| “You were quite right.” | | “Quite a few.” |

Stop means to cease and should not be used in the sense of stay. Example:

| “Do not stay long.” | not | “Do not stop long.” |

That - See which, who, that.

Transpire means to become known and is often used wrongly in the sense of occur or happen. Example:

| “It transpired that the bonds were lost.” | not | “It transpired early last evening.” |

When, where, should not be used in place of a predicate noun; when should always be used to express time, where to express place. Example:

| “Insolvency is the condition of a firm that cannot meet its bills” | not | “Insolvency is where, etc.” |

Which, who, that. Use which to refer to inanimate things and who to refer to persons. Examples:

| “The employees who signed.” | not | “The company who signed, etc.” |

| “The company which signed.” | | “The employees which signed, etc.” |

The choice of which or that is determined by sound. Examples:

| “The legislature passed the Federal Estate Tax Law that does, etc.” |

| “The legislature passed the Federal Farm Loan Act which does, etc.” |

That must not be used in place of as or so. Example:

| “We did not know it was as bad, or so bad.” | not | “We did not know it was that bad.” |

Secretarial Problems: Review and Research Questions

-

What is the distinction between “can” and “may?”

-

Furnish substitutes for the following words:

-

concern

-

couple

-

don't

-

deal

-

locate

-

What is the distinction between “who” and “which?”

-

Name five words that are frequently misused.

Secretarial Problems: Laboratory Assignments

-

Dictation.

-

Transcription.

Concrete Suggestions for the Letter Writer, part VI

Placing of Words - Be careful about the placing of words in sentences. Examples:

| “The company stands ready to deliver the bonds quickly.” | not | “The company stands ready to quickly deliver, etc.” |

| “In order fully to assure you.” | | “In order to fully assure you.” |

| “We have only ten shares.” | | “We only have ten shares.” |

| “We have received neither your letter nor your telegram.” | | “We neither have received your letter nor your telegram.” |

| “After the bonds had arrived.” | | “The bonds having arrived.” |

| “As soon as we received your order.” | | “Directly we received your order.” |

| “With reference to.” | | “In reference to.” |

| “With regard to.” | | “In regard to.” |

| “With respect to.” | | “In respect to.” |

And, but, or, should not join one idea to a preceding one unless they are coordinate; that is, similar in structure and in thought. Examples:

| “As the shortage has not been made good, we must ask you, etc.” | not | “The shortage has not been made good, and we must ask you, etc.” |

| “Although the bonds are good, you may return them.” | | “The bonds are good, but you may return them.” |

| “If the books had come sooner, we would have done, etc.” | | “The books arrived later, or we would have done, etc.” |

You - The you attitude (referring to the reader's point of view) means that the words, I, we, my, our, are subordinated as much as possible. You appeal to the man receiving the letter and no other appeal is so direct, so effective.

We, I, should not be used too often to commence paragraphs. Whenever practicable use we rather than I, especially where the letter bears the company's signature. Do not use “the writer,” “the present writer,” or “your correspondent” in place of I.

The word company should be considered singular. Example:

| “The company considers that its policy, etc.” | not | “The company considers that their policy, etc.” |

Do not ask an officer to send, ask him to have it sent.

Etc. is used for et cetera and instead of &c, and should always be preceded by a comma, and followed by a period.

Foreign terms are to be avoided as far as possible.

Secretarial Problems: Review and Research Questions

-

The following sentences have occurred in dictation given by the manager. Show in parallel columns the changes you would make.

-

There should be no misunderstanding between you and I.

-

Neither the Vice-President or President were present in the Directors' meeting.

-

Whom did you say would represent your company?

-

The corporation stands ready quickly to deliver the goods.

-

After the certificates have arrived we shall file them.

-

In reference to the inclosed correspondence.

-

The writer will personally take charge of the matter.

-

The company considers that their policy.

-

In this case the public are not to be considered.

-

Directly we received the goods we inspected them.

Secretarial Problems: Laboratory Assignments

-

Dictation.

-

Transcription.

Concrete Suggestions for the Letter Writer, part VII

Division of Words - The best usage decrees that, as far as possible, words should not be divided. When spacing makes this necessary, they should be divided as they are pronounced, by syllable.

Always put the hyphen at the end of the first line, never at the beginning of the second, and never have two divisions come at the end of two succeeding lines.

In doubtful cases it is better to divide upon the vowel. Examples:

| Pre-de-ces-sor | mem-oir | trou-ble |

| pro-duce | dou-ble |

As “X” rarely begins a word in English, do not use it to begin a syllable; use anx-i-ety. Do not use “J ” to end a syllable, as it never ends a word; instead, write ma-jes-ty, pre-ju-dice. Since “Q” always occurs in English followed by “U,” these letters should never be separated. Example: Li-qui-date.

The terminations in, ing, ed, (and plural es when they are an additional syllable) form separate syllables. Examples:

| mak-ing | dis-tract-ed | address-es |

As far as possible, avoid these separations.

The termination er when added to a verb ending with a consonant or a silent e to form a noun, also forms a separate syllable. Examples:

| Mak-er | Com-man-der | form-er |

but the termination or does not make a separate syllable. Examples:

Words like the following should never be divided:

| eleven, heaven, power, faster, houses, given, flower, prayer, only, finer, soften, liken, verses, listen, often, voyage, nothing, even, upon, etc. |

Do not end a line with a syllable of but one letter. Examples:

Secretarial Problems: Review and Research Questions

-

What is the general underlying principle governing the division of words at the ends of lines of typing?

-

In doubtful cases what is done?

-

How are such words as “shocked,” “despatched,” divided? Type the following, inserting hyphens at points where the words may be properly divided at the end of a line of typing:

| | business, including, events, capital, additional, stenographer, flower, voyage, abroad, determine, locate, making, transportation, financial, bonded, remain, proposition, release, above, nothing, former, advertising, communication, civilization, predecessor, production, difficulty, throughout, weather, cashier, advocate, alternative, company, subscriber, decision, conjunction, liabilities, congratulate, concrete, schedule, sufficient, contract, conceivable, consolidated, scarcely, deliver, percentage, concur, drawer, general. |

Secretarial Problems: Laboratory Assignments

-

Dictation.

-

Transcription.

Section IX: Form and Follow-up Letters

In every line of business an important economy is effected in correspondence by the use of what is termed “form letters” and “form paragraphs.” You will readily see that in any particular business the letters will deal more or less with the same subjects, and that a great many inquiries will be received which may be answered with the same letter. It would be a needless waste of time for the head of a company or a department to spend valuable time in dictating individual replies to every letter of this sort. Form letters are therefore constructed, covering different phases of the business - selling, adjustment claim, transportation, and the like. These are given numbers and pasted in a “form book,” a copy of which is placed in the hands of the secretaries for reference.

When a letter comes in which can be answered, let us say, with form “No. 2a,” all that will be necessary for the correspondent to do is to indicate this fact. The secretary in transcribing will simply fill in the correct name and address, turn to the “form book,” and copy letter “No. 2a.” Usually in form letters of this kind the opening paragraph is left blank so that the correspondent can dictate something that will apply directly to the particular inquiry, in this way giving the letter a personal touch.

The “form book” usually contains also “form paragraphs.” These are paragraphs that have been especially prepared to cover certain situations which experience has shown to be necessary. They also are classified by subject and numbered so that the correspondent can make up a letter by simply indicating to the secretary the paragraphs he wishes incorporated.

There is another kind of “form letter” used that is more in the nature of a circular. It makes some special announcement, solicits business, or performs the function of selling. It is usually mailed to a special mailing list, with the names and addresses of the firms filled in. Such letters are first printed by some duplicating process, such as the “multigraph,” to imitate typewriting, and often leave a word or a phrase here and there to be filled in to give the letter a more personal tone.

Many “form letters” going to a particularly high grade clientele, are reproduced with the automatic typewriter. They are actually typewritten letters, but are written by an automatic machine, such as the Hooven.

Now let us consider some of the points that are to be observed in handling this kind of work. The secretary will not have much to do with the composition of these letters. His part of the work will consist merely in writing the letters or filling in the names and addresses and placing in them such other inserts as are necessary. Form letters are intended to give all the appearance of a personally dictated letter, hence it is important that special attention be given to every detail. The names and addresses should match the duplicated form perfectly in color and density. The envelope should also match. Particular attention should be given to lining up the letters in the machine so that any inserts will be exactly in line. Carelessness in this respect and in the careful filling-in of names is one of the principal causes for complaint about form letters. If you will simply bear in mind that the form letter is to all intents and purposes the same as a personal letter, and attempt to give it that appearance, little difficulty will be experienced.

In filling in names and addresses it is an advantage to line the letter with the first line in the body of the letter and then reverse the order of writing the address, name, and date. That is, after the letter is adjusted, write the salutation, then turn back one space and write the city and state at ten (or whatever number you decide upon); turn back another space and write the street address at five; turn back again for the name, then twice more for the date. In this way the spacing will be perfect.

We need not be concerned about the ethical question of this practice of attempting to make something appear real that is not. No one is now actually “fooled by a form letter.” Its wording, if nothing else, stamps it for what it is. The details emphasized here merely make it conform to the conventions.

Secretarial Problems: Review and Research Questions

-

Name three uses for form letters.

-

In what manner are the form letters or paragraphs referred to in dictation?

-

What is the meaning of the term “follow-up letter?”

-

In what ways are follow-up letters used?

Secretarial Problems: Laboratory Assignments

-

The manager often receives requests for sample copies of expensive books. These requests cannot be granted in certain cases as the sale of the books in question is very limited. Compose a form letter which will apply to as many cases as possible and which will refuse the request in such a way that the one receiving the letter will not be offended.

-

We are to move into new quarters in a month and on account of the increased facilities which we shall have in our new quarters we shall be able to offer much better service than hitherto. Write a form letter which can be sent to all customers informing them of the change.

-

Dictation.

-

Transcription.

Mailing Lists

Nearly every business today has an accumulation of mailing lists for various purposes. If these are at all extensive and frequent mailings are made, the whole activity is handled in a special department. The secretary ordinarily will not have much to do with it. Mailing to extensive lists is usually done by means of a machine called an “Addressograph” described in another section, and the names and addresses are printed from a metal stencil. It is so arranged that names that are not of any value may be removed, or new stencils inserted whenever necessary.

In the ordinary run of the secretary's work the mailing lists will not be extensive and can usually be placed on the usual index cards and filed alphabetically, by subject, or geographically, depending upon the nature of the business and the purpose of the list. As an example: Your employer may require a mailing list of all the names and addresses of sales managers in a certain city or district. Merely record these on cards, as suggested in the foregoing, and file alphabetically under the general heading, “Bank Presidents,” or whatever the designation of the list is. The lists may be further classified by the use of colored-tab indicators, described in the filing section of this book.

Mailing lists are not of much value unless kept up to date. The information necessary for correcting filing lists is furnished by different departments. Corrections, additions, or eliminations should be made promptly. Every letter or piece of advertising matter that has been returned on account of incorrect address should be checked with the mailing list to see if a mistake has been made, and if not, and there is no way of determining the person's address, the card should be removed.

The secretary may be called upon to assist in making up such lists. There are several ways of doing this. The classified telephone book of any city of importance contains the names of dealers or firms in the various classifications, as, for example, doctors, dentists, plumbers, milliners, grocers, stationers, news dealers, and all through the range of business enterprises. It may be necessary to make up these selected lists of persons whose credit rating is favorable. The use of Dun's or Bradstreet's reference books will be necessary in doing this after the list has been made. Lists also may be obtained from firms engaged in compiling them for special purposes.

The spelling of names on mailing lists should be carefully scrutinized and checked with any original sources to verify their correctness. An immense amount of mail is wasted yearly on account either of incorrect spelling of names or incorrect addresses. The filing equipment manufacturers have worked out systems for handling mailing lists. An illustration of one of the most effective equipments is shown here.1

Secretarial Problems: Review and Research Questions

-

In what way does a mailing list continually correct itself by use?

-

What is the method of addressing the envelopes when a mailing list is very large?

-

If it is desired to have all the names on the mailing list filed together, how may the names be classified so that any one group may be picked out if the material to be sent would not be suitable for the remainder of the list?

-

How will you go about obtaining the names and addresses called for in the second Laboratory Assignment given below?

Secretarial Problems: Laboratory Assignments

-

Compile a mailing list of not more than fifty of the most important businesses in your city as follows:

-

Banks

-

Physicians.

-

Milliners.

-

Manufacturers.

-

Druggists.

-

Machinery houses.

-

Compile a mailing list of the important automobile manufacturers of the United States.

-

Dictation.

-

Transcription.

Section X: The Technique of Telephoning

If the telephone exchanges of the country suddenly shut down, business would stop. The telephone is an indispensable adjunct to business.

The object of the telephone is to save time. Using the telephone properly is a very important duty in a secretary's activities, and the following instructions ought to be studied carefully. The first problem to be considered in using the telephone is the instrument itself, because of the fact that it is used by human beings. To use a quotation from the instruction book of the telephone company: “In telephone operating the human element must be considered. The public is human. The telephone operators are human. The spoken word and its inflection convey whatever impression each gets of the other. Under such conditions, courtesy both on the part of the operating force and the public is like oil to machinery - necessary to prevent friction.”

There is a technique in telephoning, as there is in everything else connected with business. Before signaling “Central,” look up the number and exchange carefully. The names in the telephone directory are arranged alphabetically. The name is followed by the street address, and exchange name, and finally the number. The New York telephone directory gives the following compact and easily-understood directions for using the telephone:

Calling Numbers - When giving a number to the operator state:

-

The name of the central office wanted;

-

each figure of the telephone number;

-

the party line letter if there is one.

Numbers which are even hundreds or even thousands should be given as such instead of each figure being given separately.

| Examples: | As pronounced |

| CAN al-0027 | Canal oh-oh-two-seven |

| JOH n-1253 | John one-two-five-three |

| MAI n-2125-J | Main two-one-two-five-J |

| BRO ad-4800 | Broad four-eight-hundred |

| WOR th-5000 | Worth five-thousand |

After giving the number, listen to the operator as she repeats it. If she repeats the number correctly, say “yes” or “right.” If she does not repeat the number correctly, say “no” and give the number again.

If you are calling from a party-line message-rate station, announce the letter of your station if there is one after giving the number as above. Example: This is J calling.

After calling a number remain with the receiver at your ear until the called number answers or until you receive a definite report.

While you are waiting for the called number to answer, the intermittent burr-rr-ing sound of the ringing signal will indicate that the work of putting up the connection has been performed by the operators concerned.

To call back the operator, move the receiver hook up and down slowly.

Do not hang up the receiver until you are ready for the operator to take down the connection.

Courtesy in Telephoning - When answering the telephone it is superfluous to say “Hello!” “Who is that?” “What do you want?” Merely give the name of your firm. One of the first questions for the secretary to ask when responding to a telephone call is “Who is speaking, please?” Before any information is given be sure of the person speaking and determine whether or not he is entitled to the information. Even the obvious information of whether your employer is in or not should not be disclosed until you know with whom you are speaking.

In speaking a low, well modulated voice will carry much better than one that is pitched high. This is especially necessary if you are in an office with others. Your voice should not be raised above normal; if anything, talk in a lower tone than you are accustomed to use in speaking, and speak slowly. Half the art of good telephoning lies in deliberate talking. It gives clearness and emphasis.

Your manner should be as courteous as if you were talking face to face. Many people seem to think that to be ill mannered in telephone conversations is to be businesslike. Make your messages brief, but clear and definite.

When you telephone, devote yourself to telephoning. The attempt to carry on other tasks at the same time causes you to move away from the transmitter and the person with whom you are talking will not hear distinctly, or may misunderstand you altogether.

“Busy” Signal - If you get the “busy signal” when calling, wait a few minutes and try the number again. Nothing is to be gained by placing the blame on the operator for your failure to get a number. As a general rule telephone operators do everything in their power to give service.

Long Distance Telephone - When it is necessary to call someone in a different city, take off the receiver and ask the operator for “long distance.” The New York City telephone directory gives the following instructions for making a long distance call:

When the Toll or Long Distance Operator answers, give her the following details:

-

The telephone number from which the call is made and your name, if you desire to give your name.

-

The number of the telephone desired, if known.

-

The firm name or the name and initials of the person under whose name the telephone is listed and the street address, if the telephone number is not known.

-

The name of the person with whom you wish to speak.

-

The name of the alternate person, if you are willing to talk with anyone else in case the person desired cannot be reached.

-

The name of the city or town and state in which the person desired is located.

Remain at the telephone until the operator indicates that you may hang up the receiver.

Automatic Telephone - In many cities the automatic telephone is now installed. With the automatic you call your own number. The telephone directory of the city in which you are located describes the use of this instrument. If you have had no experience in using the automatic, read the description of the instrument and how it is used. It would be impractical to give here a description of the automatic, for not only is it technical, but the instruments used vary.

Secretarial Problems: Review and Research Questions

-

Give the steps necessary in calling a number.

-

Give the steps necessary in answering a telephone call.

-

How are the best results obtained in making yourself understood when telephoning?

-

What other operations can be carried on while telephoning?

-

What is meant by “long distance”?

-

What is an automatic telephone?

Secretarial Problems: Laboratory Assignments

-

The manager will make definite assignments to be carried out by you.

-

Dictation.

-

Transcription.

The Technique of Telephoning, part II

Secretarial Technique - From the secretarial point of view the telephone call must be handled similarly to a call at the office. But you do not have the advantages of seeing the person addressed and judging him. You must get all your impressions from the information he gives, his voice, manner, etc., so far as you are able to judge from his conversation. You must be the judge whether you will connect the caller with your employer's telephone. He may have left word with you that he is “in conference,” or so busy with important matters, that he does not wish to be disturbed even by a telephone call. In such cases try to give what information you can, handling the matter as skillfully and tactfully as possible, and submitting a memorandum of it to your employer later. You may inform the caller that you will ask your employer to call him when he is free.

The secretary will be called upon many times to attend to business matters by telephone. He should see to it that he has complete and definite instructions as to just what is to be done, making a shorthand note of it if it is extended. The secretary will also be required many times to call numbers and to get a certain person on the wire. This should be done as expeditiously as possible. Particular attention should be given to transferring the wire to your employer at once, so that the person at the other end of the wire will not be kept waiting. Many executives object seriously to being called in this way and it does not help matters if they are kept waiting even for a few moments. Frequently this transfer can be made without a word passing between the secretary and the person making the call. As soon as the person asked for responds, the telephone can be transferred to the employer without speaking.

Handling Calls for Others - If it is your duty to answer the telephone for a number of people in the office, it will be necessary to hold the wire while you communicate with them. Occasionally you will lose your connection in doing this. It would be well in all cases to try to ascertain who is calling, merely asking “Who is calling, please?” In many instances this will enable you to re-establish connections should the calling number not make the attempt again. If the person being called is not in the office, suggest taking the message for him. At least try to secure the name and telephone number of the person calling.

It is necessary at times to “hold the wire” when looking up information in the files or elsewhere. If it is information that will require some time to look up, say that you will call back as soon as you have secured the information wanted. Many times you can switch a “party” to another department where the call properly should go. In doing this ask the caller to hold the wire until you can establish the connection through the switchboard operator. You will use the same care in trying to secure information as you would if the caller were in your office asking to see your employer.

Always keep a pencil and pad convenient while telephoning, to make a note of any matters that will require further attention. Messages received in the absence of your employer should be accurately written, attention being given to obtaining the name of the caller, his telephone number, and any message he wishes to leave. This should be brought to the attention of your employer in the form of a memorandum. In some offices a blank for this purpose is used.

Finally, the business telephone should not be used for private messages. The secretary will discourage his friends from calling him during business hours and he will also refrain from using the telephone for his own convenience, during office hours or afterward.

Secretarial Problems: Review and Research Questions

-

What is the first thing to ascertain when answering a telephone?

-

Give the important points to be observed in answering the telephone when your employer is wanted.

-

Outline the technique to be followed in giving instructions by telephone.

-

What is the plan to be followed in “holding the wire”?

-

In your employer's absence what procedure is followed when a telephone call for him is received?

Secretarial Problems: Laboratory Assignments

-

The manager will make definite assignments to be carried out by you.

-

Dictation.

-

Transcription.

Section XI: Bills, Invoices, and Statements

The development of mechanical bookkeeping has been one of the most important features in the history of the typewriter. The making out on the typewriter of bills, statements and invoices, along with accounting statistical work, has now become a highly specialized field. In a general instruction book an extended treatment of the subject is impossible, even if it were desirable; but since every secretary is called upon to do more or less work of this kind, practice in the simpler forms of billing is necessary. In the offices of small firms and in offices where a regular bookkeeping department is not a part of the organization, more or less billing will fall to the duty of the secretary.

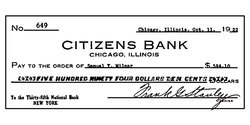

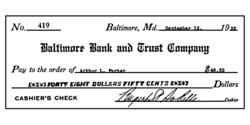

The most common form of billing which the secretary will encounter is a simple itemized statement of purchases made, either at one time or during the month, the price of each purchase, and the “extensions.” An extension is simply the total of any one item carried over to the dollars and cents column. For example, one item will be recorded thus: “64 yards taffeta at $1.49 . . . . $95.36.” The extension will be the total amount of this purchase, or $95.36. When all of the items have been thus figured, the grand total is given at the bottom of the column, as shown in Figures VII and VIII. Bills may be made up from the sales slips, from the orders themselves, or from data furnished by the bookkeeping department. They may be prepared in duplicate or triplicate, as the case may require, by the use of carbons. While the general plan of billing is quite well standardized, forms vary considerably.

In making out bills all debit items should be written with a black ribbon and whenever possible the credits with a red. A credit is made if an article is returned or a part payment is made on the bill. Bills are written on regular blanks called billheads which, as shown in the illustrations, give the name of the Company, the date, the terms of payment, and other information that the purchaser should know.

Bills for merchandise are usually known as invoices. Statements are generally sent out by business houses to their customers at the end of the month. A statement is in the form of a bill or invoice, but it usually gives the dates of the invoices and the total amount due instead of the particular items purchased and the price of each. Bills and statements are generally written on special machines equipped with capital letters only; very little punctuation is used; ruling is reduced to the minimum. The important factors are accuracy of statement and of figures. In the ordinary office most of the billing will be done on the regular correspondence machine. The secretary should familiarize himself with the forms used and the methods in effect in the office in which he is employed.

Methods of Billing - The method of billing known as the retail bill and charge, is used largely by retail houses, such as department stores. In this method bills are prepared in duplicate by the use of a carbon sheet. The first time a purchase is made during the month the items purchased are recorded on the billhead. The bill, carbon, and second sheet are then filed alphabetically under the customer's name. When additional purchases are made, they are recorded on the bill as previously explained. The sales are totaled each day and at the end of the month the totals are added, the original bill detached and mailed to the customer. The carbon is placed in a loose leaf binder for the records of the accounting department.

“The Unit Billing System” is a name applied to the method by which several carbon copies are made of each bill, the number of copies depending upon the circumstances.

“Condensed charging” is a term applied to the method used by wholesale companies. By this method a carbon copy of the bill is made on a sales sheet which remains in the machine until it is filled, the sales sheet simply showing the names, items, and amounts of purchases, the object being to save space on the sales sheet. The sales sheet, which remains in the machine, contains items purchased by various customers. A special type of machine with wide carriage is required.

Secretarial Problems: Review and Research Questions

-

When making out bills on the typewriter, a two-color ribbon (red and black) should be used. What parts of the bill are to be written with each color?

-

What are the distinctions between “bills,” “invoices,” “statements”?

-

What is meant by “dating” as in the expressions “60 days' dating,” “90 days' dating,” etc?

-

What style of type is generally used in billing?

-

What is meant by “condensed charging”?

Secretarial Problems: Laboratory Assignments

-

The proper blanks for the following bills will be found in the Exercise Book. The addresses will be furnished by the manager. Carry out the extensions. If an adding machine is available, the totals may be obtained through its use. Otherwise, they will have to be added mentally.

-

Sold to Miss Emma A. Hale. 1 Silk umbrella, 12.00; 6 pr. Black silk stockings, 9.00; 1 Taborette, 4.95; 1 Salad set, 2.75; 1 Bedroom tea set, 7.25; 1 Silk Sweater, 26.45; 1 Fan, 14.00; 1 Toaster, 6.75.

-

Sold to the Copley Plaza Hotel. 60 doz. Towels @ 5.00; 10 doz. sheets, 54 x 90, @ 12.00; 20 doz. Pillow cases 44 X 36, @ 4.80; 300 yds. Pantry toweling, @ .21; 220 yds. Dish toweling @ .23; 480 yds. Glass toweling, @ .18.

-

Sold to the Hotel Mohican. 4 Mahogany tables, 36 x 48 @ 23.70; 6 Mahogany tables, 54 x 78 @ 29.80; 3 Golden oak tables, 28 x 36 @ 18.10; 3 Golden oak tables 38 x 70 @ 23.75; 12 Mahogany chairs @ 6.75; 22 Golden oak chairs @ 5.80; 3 Golden oak chiffoniers @ 12.30; 2 Golden oak dressers @ 12.80; 3 Mahogany dressers @ 11.90.

-

Sold to Mr. F. L. Sterbenz. 1 Brake lining, 1.80; 4 Inner tubes, @ 5.00; 1 Leather shoe, 3.25; 1 Speedometer, 30.00; 1 Baggage carrier, 5.00; 3 Quarts oil @ .45; 3 Vacuum cup tires @ 20.00.

-

Sold to Mrs. S. A. Everett. 1 doz. Eggs, .51; 5 lbs. Granulated sugar @ .09; 1 gal. Maple syrup 1.50; 1 doz. Soap, 3.65; 3lbs. Ceylon tea @ .75; 5 lbs. Graham flour @ .24; 1 Cabbage, .10.

-

Sold to Mrs. Walter L. Keller. 1 Gold mesh bag, 230.00; 1 Wrist watch, 125.00; 1 Fan chain, 18.00; 1 Cigar case, 47.00, 1 doz. Coffee Spoons, 14.00; 1 Bread tray 12.00.

-

Sold to Burton & Lane. 1 doz. Blue pencils, .59; 1 gross Venus pencils, 4B, 11.00; 1 Glass desk pad, 12.60; 2 quarts Ink @ .70; 1 doz. 1080 erasers, .40; 2 Oak letter trays @ .75.

-

Sold to Cahill & Price. 1 Filing cabinet, 30.00; 3 Typewriter chairs @ 8.00; 6 Mission chairs @ 8.50; 4 Typewriter tables @ 10.50; 1 Oak roll top desk, 94.00; 40 yds. Brussels stair carpet @ 3.50; 1 Mahogany arm chair, 31.00.

-

Sold to The Wilson Stores Company. 112 doz. Tea cups @ 2.20; 108 doz. Saucers @ 1.88; 87 doz. Coffee cups, large @ 3.12; 92 doz. Saucers @ 2.10; 37 doz. Demi-tasses @ 1.97; 21 doz. Saucers @ 1.40; 312 yards. Sheeting @ 71; 380 yds. Cheesecloth @ .08.

-

Sold to The City Furniture Company. 215 Oak chairs @ 5.29; 198 Mahogany chairs @ 6.85; 45 Kitchen tables 48 x 60 @ 4.92; 20 Kitchen chairs @ .87.

-

Make out a monthly statement for exercises c, d, g, i and j, given in the foregoing.

Note the following returns for credit:

-

By the Hotel Mohican: 3 Mahogany chairs @ 6.75.

-

By Mr. F. L. Sterbenz: 2 Inner tubes @ 5.00; 1 Vacuum cup tire, 20.00.

-

By The Wilson Stores Company: 14 doz. Saucers @ 1.88, 4 doz. Coffee cups @ 3.12.

-

Dictation.

-

Transcription.

Section XII: Forms of Remittance: Business Forms

In all businesses the exchange of money, or documents representing money, titles to goods, and the like, is constantly going on. Definite knowledge about the different forms of remittances, how they function in business, and the use of each in a given situation, is essential because much of the correspondence will deal with these. In practice the secretary may have the actual handling of many of the remittances to be inclosed in letters while making up the mail, or in taking care of the details of his employer's business.

In business correspondence and reports constant reference is made to checks, drafts, acceptances, certified checks, postal money orders, and express money orders. The secretary must not only be able to recognize at once the meaning of these terms, but should understand the purpose of these various instruments in business.

The most common forms of remittances are: Personal checks, bank drafts, cashiers' checks, certified checks, postal money orders, express money orders, registered letters containing cash, certificates of deposit, and postage stamps.

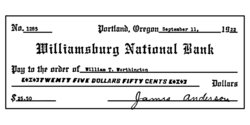

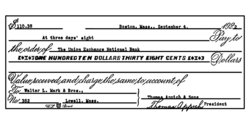

The Personal Check - The personal check is perhaps the most common form of remittance. When used for remittances from one city to another, banks as a rule make a charge for handling, known as exchange. A personal check is simply an order on a bank for the payment of money to a designated individual, firm, or corporation, drawn by one not a banker, who has funds on deposit in a bank. See Figure IX.

Checks should be made out on the form supplied by the bank with which one does business and should be made “payable to the order.” All checks are made “payable to the order of (the name inserted)” to make them negotiable and also as a matter of protection. A check “payable to order” is payable to the individual, firm, or corporation, to whose order it is drawn. If the holder of a check wishes to transfer it to another, he writes on the back of the check “pay to the order of ............”in blank” by signing his name on the back, without specifying to whom the check is to be paid or he may qualify his indorsement by writing the words “Without recourse” and sign his name underneath them. This form of indorsement releases the indorser from further liability of payment. It is then payable to anyone who presents it at the bank for payment, although most banks will not cash a check unless the person presenting it is personally known at the bank or can be properly identified.

If a check is to be drawn so that the bearer may cash it without identification, draw it “payable to order” have the person indorse it, and then write under the signature the words “Signature O. K.” and indorse it yourself.

A check drawn “payable to the order of bearer” may be cashed by anyone who presents it to the bank. A depositor who wishes to draw money from the bank himself can draw the check “payable to the order of cash” or to his own order, indorsing it if the latter. A check drawn payable to cash is payable to whoever presents it, but usually only after identification. It is preferable to draw checks to “order” instead of to “Cash”.

In writing a check, observe carefully the following points: The check should be numbered to assist in accounting for each one, and in comparing with the stub. Wherever possible make checks payable to the individual, corporation, or firm to whom the money is to be paid. Write the name of the payee (the person to whom the check is payable) after the printed or engraved words “pay to the order of.” After the dollar sign, write the amount of the check in figures, using care to begin the first figure as close to the dollar sign as possible to make the figure clear and unmistakable. The figures should be compact so that it will be impossible to fill figures in between them. Write amounts thus: 500-75/100. In the space preceding the word “dollars,” write the amount spelled out, as “Five hundred eleven and no/100.” The amount in figures should always agree with the written words. The signature on a check and elsewhere should always be the same. For example, if the name were “William B. Johnson,” it should not be written variously “Wm. Johnson,” “William Johnson,” “Wm. B. Johnson.” A name is preferably written in full; at least a definite way of writing a signature should be adopted and not varied.

The suggestions given in the foregoing for drawing checks are for two purposes: To facilitate handling and to avoid errors and confusion; and to guard against raising the amounts. The amounts on checks issued by business houses are usually written with a check protector. These perforate the amounts in the paper, making alteration more difficult, but are not a positive protection against raising. Most checks are printed on what is known as “safety paper.” This guards against erasures. An erasure on a check printed on safety paper, either by mechanical means or ink eradicator, is at once noticeable and renders it void so far as the bank is concerned. If a mistake in writing a check is made, the check should be destroyed and a new one made out.

Payment on checks may be stopped before presentation by notifying the bank not to pay, giving the bank the number of the check, the amount, the name of the payee, and the details concerning it. A check may be written on an ordinary piece of paper and it will be good if you have funds in the bank on which it is drawn, but it is not good business practice to draw checks in this way. Always use the forms provided.

A check may pass through several hands and contain many indorsements before being presented to the bank for collection.

A check should not be used in paying a bill to those unacquainted with the credit or financial standing of the remitter. A personal check should not be indorsed to another unless the indorser is sure that it is good. When paid, a personal check is a receipt for the amount. For this reason it is widely used in paying current bills by nearly everybody who has sufficient funds to establish a bank account. The advantages of having a checking account are so obvious that everyone should make provision for such an account.

What is said about checks in the foregoing applies to all checks so far as filling in names, amounts, and the like are concerned.

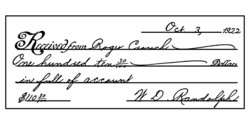

Indorsements - All indorsements must be placed on the back of a check. To indorse a check, the name of the payee is written by him across the top of the back, directly below the perforations. The top of a check is the left end of its face. The name in the indorsement should be identical with that on the face of the check. For example, if the name appears on the face as Jno. Gregg, the indorsement should be Jno. Gregg, and not John R. Gregg. If the name on a check is incorrectly spelled it should be indorsed twice, first, as the name appears on the check, and then correctly. If a check is intended for deposit in a bank, write “for deposit” and the name of the bank in which it is to be deposited above the indorsement. This is done as a matter of protection. Should such a check be lost the finder would be unable to cash it, which he might do if the check were indorsed in blank. Business houses use a rubber stamp for indorsements on checks for deposit. See Figure X.

Voucher Check - Many business houses have a blank space on their checks in which is written the purpose of the check - as, for example, “Salary for December 1922.” This is known as a voucher check.

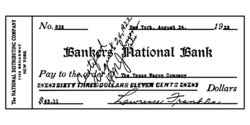

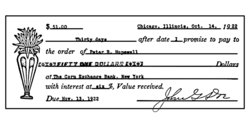

Certified Check - A certified check is simply a personal check which has been presented to the bank by the drawer and certified. When a check is presented to a bank for certification, the cashier of the bank upon which it is drawn writes or stamps upon its face “Certified,” or “Good when properly indorsed,” and signs his name. The amount of the check that has been certified is charged to the depositor's account at the bank, the same as if he had personally drawn the money. A certified check carries the bank's guarantee of payment. It may be used for remittances, the same as a bank draft, but it is usually subject to an exchange fee.

A certified check is often required in business, not only for remittance purposes, but to pay a note at some other bank than the one in which the depositor has funds, to buy real estate, or for other purposes, because it carries the bank's guarantee of payment, which is not the case with a personal check.

The bank will only cash a personal check when there are funds on deposit to meet it. A bank upon which a check is drawn will generally certify it if requested, no matter who presents it, provided the drawer has sufficient funds on deposit to cover the amount. See Figure XI.

Secretarial Problems: Review and Research Questions

-

What is a personal check?

-

Give briefly the chief points to be observed in making out a personal check.

-

What is meant by indorsement? Explain the indorsements on a check, where made, and why.

-

Explain the meaning of “payable to order.”

-

How may the payment of a check be stopped?

-

May a depositor draw money on his own check? Describe the method of making out such a check.

Secretarial Problems: Laboratory Assignments

-